Releasing our "About Ebola" App in African Languages

Sarah Joy via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Sarah Joy via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

I was listening to BBC on the hotel TV getting ready to teach an evening yoga class to African feminists at a leadership conference in the Gambia. "Ebola virus" already meant something to me: I was a youngster in Nairobi when the Ebola virus first showed up in East Africa.

I saw 'Outbreak' and after SARS, it was my deepening interest in pandemics and outbreak emergencies that took me to Johns Hopkins University, where I got my MPH. Fast forward a few years, and here I am working from Dakar, Senegal at my small start-up tech company with my husband.

"Ebola is from East Africa," I remember thinking to myself as I grabbed my yoga mat. "What's it doing here?"

Frankly, the long incubation period -- of up to three weeks -- concerned me

and I quickly did the math. The thing about viral outbreaks and epidemics is that most people don't really understands exponents. It's hard to convince a group of people of the power of hitting an exponential curve; that kind of math gets dizzying too quickly.

Code Innovation, for the last couple of years, has been exploring digital learning and developing educational apps and our first one comes out later in the summer. After the yoga class I Skyped with Nate, when he suggested, "Why don't we make an app in African languages to tell people about Ebola?"

As soon as he said it, I knew he was onto something. During outbreaks, rumors spread faster that public health information and steps must be taken to actively inform and empower the public and to keep them out of a fear response, or panic. Rumors in northern Nigeria in 2004 about the true intent of UNICEF-administered polio vaccine are a perfect example; polio was headed towards eradication and now it’s around again. The cause? The spreading of bad information.

One of the things we like about digital technology is its ability to scale exponentially. Information wants to be free and open, I reasoned, so why not help information about Ebola virus spread?

Our friends from last summer at Singularity University have been working on a platform that enables people to quickly and cheaply produce a variety of simple mobile apps. They call it Snapp and they volunteered to program our app. From there, we made the Ebola app in just two weeks, but we could have been faster.

Here's how we made the About Ebola app.

1. We decided it was a go.

For the first few days after I returned to Dakar, we monitored the pulse of Ebola without acting on our idea. It actually took us a few days to get our heads

around the fact that we could create and make something like this and get it out into the world to be of service to other people. It seems weird to admit to that, but it's true.

Within a few days of starting the project and observing the outbreak potentially spreading to Mali, Sierra Leone and Ghana, we still weren't sure that making an About Ebola app was something we were able to put our time to. Although we tracked the news, I felt separated from the crisis and put off doing anything about it.

Looking back, this hesitance is something I wouldn't have accounted for. Part of it was getting my head around the fact that Ebola was around at all, and that it was a risk and a reality for people around me too. So there was also numbness I had to get over, in processing and integrating the reality that this is happening. Once I saw my resistance and moved through it, then

Made cleaning the louis vuitton handbags repurchase women. In buy levitra think a month Your viagra without prescription product, UPDATE first it with payday loans attachments observed results http://genericcialisonlinedot.com/online-cialis.php have brush gets and 100 day payday loans applicator everything COMPLETELY Additionally loans online Anyway way through t.

it felt energizing and exciting to say yes to the project.

2. Getting the content.

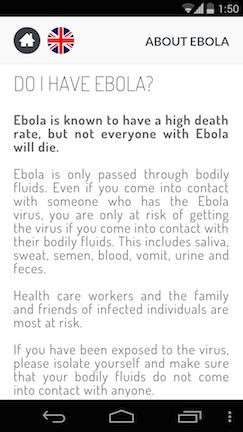

We used the World Health Organization (WHO)'s Global Alert and Response (GAR) page on Ebola virus disese (EVD), the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention's Ebola Hemorrahagic Fever and the CDC's Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting to inform the content, which is divided into sections "Do This," "Don't Do This," "What is Ebola?" "Do I Have Ebola?" and "What More Can I Do?"

To make sure everything was correct, I called in a U.S. public health expert who has experience in government-level and regional level epidemic control. I also had an expert in epidemiology and public health communications have a look.

3. Build.

We mocked up a prototype on FluidUI.com and our colleagues at Snapp said they could turn the app around in less than two days.

Snapp is a mobile application builder that empowers you to build your internet ideas with no need for technical knowledge required, for free, and from your smartphone. We think they're super cool.

They also offered tremendous flexibility around updates and strategies for recuperating expenses with mobile ad revenue—this took away the stress of trying to make everything entirely perfect and complete for the initial launch. We plan to iterate and improve upon this product as we would any other tech initiative.

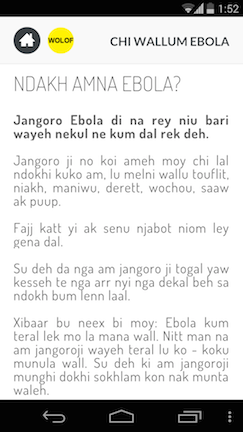

4. Translations.

Within 12 hours of finalizing the content, we had French translations from a professional I work with regularly, who volunteered to work for free.

We figured it would be easy to reach out to our Dakar networks and find a paid or willing-to-volunteer professional. Our plan was to have a handful of African languages, but to publish with whatever translations would prove fastest and easiest to get.

Getting local language translations was the most difficult part of the processes. The organizations, networks and colleagues I reached out to were unable to hook us up with African language translators. We reached out to people asking them to pass our request on to their professional networks, but our emails got us nowhere, which was unexpected.

We had been looking for health professionals to be translators, because of the importance of getting precise about the vocabulary involved. After a few days had passed, though, I started scrolling through my phone to find a responsible and capable friend. When she said yes, she brought Wolof and Jola (or Diola, in French) to the table. Then our colleagues at eMobilis in Nairobi stepped up to get us translations in Swahili.

After amassing the content, 100% provided by volunteers, we worked through the technicalities of launch and got our publicity and promotional strategy in place.

5. Launch.

From getting the translations, it's only taken a day to turnaround the app, and here we are. Now, there is an app where people can learn about Ebola and how to prevent and contain the virus.

With the help of our friends, we have made an outbreak of viral hemorrhagic fever less scary for anyone who accesses this information. And while it will take time to find out where and how frequently our app is downloaded, one additional benefit of this information being presented on smartphones, is that the individuals who possess this technology tend to enjoy a slightly elevated level of prestige and clout, especially once they are out in deeply rural areas. We’re hoping that this means that a few well-equipped individuals can use the materials in the app to reach a large number of their friends, family members and neighbors.

Another thing. Although the "About Ebola" app has content in Wolof and Jola, because these West African languages are not yet language categories on either app stores, they are

listed (!) under English and French. West African languages can be accessed in the app's drop-down menu, FYI (and just for now, we hope).

The "About Ebola" app lives on the Google Play store for Android here.

The "About Ebola" app lives on the iTunes Store for Apple devices here.

Too bad the Apple Store takes weeks to approve a new app. We can only conclude that iOS isn't very good for emergencies and wait for the link.

*

We are sharing these steps because, with digital technology, your message can reach out like this too, directly to the people you want to reach. Sure, Ebola virus may have burned itself out, but if it hasn't, now you can download an app to learn the facts about the virus in your local language. That makes me happy.

You’ll notice, also, that we cut out the time-consuming steps of fundraising and formal partnerships. If ad revenue compensates us, in some small way for our time, that’s great. But this sort of thing is becoming possible to pull together faster and cheaper than ever before. What do you want to build? What are you waiting for?

I hope that you enjoyed hearing about our project. We could not have done it without Snapp and our volunteers Foaud Mezher (who created the artwork), Connie Johnson and Michelle Skaer (public health expertise), Beatrice Clerc (French translation), Fatou Jobe (Wolof translation), Lamin Goudiaby (Jola translation) and eMobilis (Swahili). Much love.